The Shrine Hills, located at the urban center of Davao city, finds a similar case with that of the Cherry Hill Subdivision in Antipolo City, which tragically resulted in 59 lives lost and hundreds of families lost due to landslide in 1999. Land and subdivision developers are very eager to develop the area as it is strategically located in the middle of the City. Here’s what environmentalist groups’ response to the position paper submitted by DMC URBAN PROPERTY DEVELOPERS, INC. (DMC UPDI) ON THE PROPSED AMENDMENTS TO THE CITY ORDINANCE NO. 0546-2013.

In August 3, 1999, at least fifty-nine (59) lives were lost and hundreds of families left homeless at Cherry Hill subdivision in Antipolo City [1]due to landslide. It was a tragic reminder that nature can teach us valuable lessons in the hardest and harshest way.

Until now, those who are responsible for the incident is yet to be made accountable for the loss brought by this tragic event. Worse, residents of Cherry Hills subdivision and the developers are blaming each other. The latter for using substandard materials for the low-cost housing project and the former for the renovations they made in their houses [2].

It was a tragedy no one wants to happen in their own place. Thus, measures to prevent this from happening should be taken. One, is the proper zoning and land use plan.

In Davao City, the Shrine Hills, located at the Urban Center of the City, finds a similar case with that of the Cherry Hill Subdivision in Antipolo City. Land and subdivision developers are very eager to develop the area as it is strategically located in the middle of the City.

More than Shrine Hills’ natural aesthetic, it serves as the City’s lungs that provides clean and breathable air for all Dabawenyos. Also, it serves as a home and resting grounds for different species of birds and other terrestrial animals. Shrine Hills also serves as an escape for Dabawenyos for all the hassle and bustle of the City as they enjoy its scenic beauty and tranquility. For all that it has provided us, it is only right to protect and save Shrine Hills from all the threats brought about by human activities.

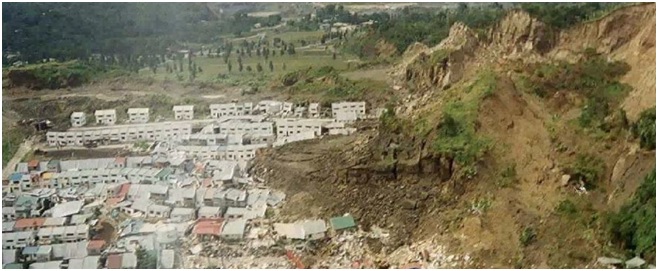

Last year, Shrine Hills made headlines in newspapers, TV and radio news in Davao City,not for all the good reasons as it should be, but for the unfortunate incidents that could have been prevented in the first place. In the night of October 5, 2017, due to insistent rain, a portion of Shrine Hills eroded endangering the lives of those living above and below it. It also caused stressful inconvenience to commuters caused by heavy traffic as the local government unit of Davao City and the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) were prompted to close the Diversion Road.

The City Council even allotted time in its regular session to discuss the matter and to conduct an inquiry as to what really happened, what caused the sudden landslide, and who shall be made responsible.

Shrine Hills is a disaster waiting to happen and the least we want to happen in Shrine Hills is the tragic event the Cherry Hill Subdivision had experienced. Now, more than ever, is the right time to regulate the developments in the area so as not to endanger the lives of the Dabawenyos. We cannot truly say “LIFE IS HERE!” if our life is threatened with a disaster in our pursuit of development for our city. The incident in Antipolo 19 years ago and the recent warnings should be a lesson for all of us.

ISSUES RAISED IN THE

POSITION PAPER OF DMC UPDI

Considering all the arguments raised in the position paper of DMC UPDI in opposing the proposed amendments to the City Ordinance No. 0546-2013, the following issues may be inferred.

- Whether or not City Ordinance No. 0546-2013 is Constitutional; and

- Whether or not the proposed amendment is violative of the due process and equal protection of the law.

FIRST ISSUE: CONSTITUTIONALITY

OF CITY ORDINANCE NO. 0546-2013

It is erroneous for DMCI UPDI to “implore the SangguniangPanlungsod to abandon the provisions of the 2013 Ordinance and proposed amendments that effectively prohibit DMC UPDI from pursuing development projects involving its more than 26-hectare property in Shrine Hills[3].”

Questions with regard to the Constitutionality of an ordinance must be assailed to the proper Court in a judicial proceeding. The Sangguniang Panlungsod, should it decide on the issue, will be acting in excess of its authority – ultra vires – as it is not within its mandate and power to pass upon the Constitutionality or not of an Ordinance.

The judiciary through the courts has the power to decide on issues involving the Constitutionality of an ordinance. In the case of Philippine Migrants Rights Watch, Inc. vs. Overseas Welfare Workers Administration [4], the Supreme Court ruled that the Regional Trial Court (RTC) has jurisdiction to resolve the Constitutionality of the statute, presidential decree, executive order, or administrative regulation, as recognized in Section 2(a), Article VIII of the 1987 Constitution, which provides:

Section 5. The Supreme Court shall have the following powers:

xxx xxxxxx

(2) Review, revise, reverse, modify, or affirm on appeal or certiorari, as the law or the Rules of Court may provide final judgments and orders of lower courts in:

(a) All cases in which the constitutionality or validityof any treaty, international or executive agreement, law, presidential decree, proclamation, order, instruction, ordinance, or regulations in question. [4]

Considering the foregoing, DMCI UPDI assailed the Constitutionality of the Ordinance before a wrong venue.

Further, this act in questioning a valid enactment of a duly instituted authority before the body who enacted the same is an upfront to the authority and power vested upon it by the Constitution and the Local Government Code, as a legislative body of the City, to “enact ordinances…for the general welfare of the City and its inhabitants pursuant to Section 16 of the Local Government Code.”[5]

Should the SangguniangPanlungsod grants the appeal of DMC UPDI, it will open the gates to more “Legislative Adjudication” sans Judicial Review on the Constitutionality of an ordinance. This will result to an encroachment of the legislative body of the powers of the judiciary. More so, it will negate the long standing principle of the presumption of constitutionality that all laws, including ordinances, enjoy the presumption of constitutionality.

As Justice Malcoml Categorically expressed: “The presumption is all in favor of validity…. The action of the elected representatives of the people cannot be lightly set aside. The councilors must, in the very nature of things, befamiliar with the necessities of their particular municipality and with all the facts and circumstances which surround the subject and necessitate action. The local legislative body, by enacting the ordinance, has in effect given notice that the regulations are essential to the well-being of the people…[6]”. (emphasis supplied)

GRANTING ARGUENDO, that the legislative body can pass upon the constitutionality of an ordinance, DMC UPDI is already barred from assailing the same due to estoppel by laches.

Laches is defined as “the failure or neglect, for an unreasonable length of time to do that which by exercising due diligence could or should have been done earlier; it is negligence or omission to assert a right within a reasonable time warranting a presumption that the party entitled to assert it has either abandoned it or has declined to assert it.[7]”

It should be noted that the City Ordinance 0546-2013 was enacted five (5) years ago. DMC UPDI has all the time from 2013 until now to question the validity or constitutionality of the ordinance but they never did for reasons they did not even mentioned in their position paper.

The Constitution, the Local Government Code, the Rules of Court and Jurisprudence give them the remedies available to them when the ordinance was passed. Even before the Ordinance was passed, the Rules of Court provides them with the remedy should they want to question the said measure. Again, for reasons unknown, they did not question or oppose the same.

Had the amendments to the City Ordinance No. 0546-2013 not introduced, they would not have questioned the Constitutionality of the Ordinance.

SECOND ISSUE: PROPOSED AMENDMENT

VIOLATES THE DUE PROCESS AND EQUAL

PROTECTION

Before we discuss the second issue, we will first discuss the sub-issue on WHETHER OR NOT THE PROPOSED AMENDMENT IS A VALID EXERCISE OF POLICE POWER OF THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT UNIT and WHETHER OR NOT JUST COMPENSATION MUST BE PAID.

Legislative power is vested in the Congress of the Philippines which is composed of the House of Representatives (Lower House) and the Senate (Upper House) [8]. However, such power is delegated to the Local Government Units through the decentralization of powers. As recognized in Section 3, Article X of the 1987 Philippine Constitution, which provides:

Section 3. The Congress shall enact a local government code which shall provide for a more responsive and accountable local government structure instituted through a system of decentralization…allocate among the different local government units their powers…powers and functions and duties of local officials….

In Legaspi vs. City of Cebu[9], the Court declares the importance of decentralization. It held that “The goal of decentralization of powers to the Local Government Units (LGUs) is to ensure the enjoyment by each of the territorial and political subdivisions of the State of a genuine and meaningful local autonomy.”

Such decentralization of power is manifested under Section 16 of Republic Act 7160 otherwise known as the Local Government Code which provides that, “Every local government unit shall exercise the powers expressly granted, those necessarily implied therefrom, as well as powers necessary, appropriate, or incidental for its efficient and effective governance, and those which are essential to the promotion of the general welfare” (emphasis supplied). The Code further provides the duty of every local government unit to “promote health and safety, enhance the right of the people to balanced ecology…and preserve the comfort and convenience of their inhabitants]”

It is through Section 16 of RA 7160 that the Local Government Units are given the Police Power which was initially inherently reserved to the National Government. The LGC also provides for the liberal construction of the general welfare clause to “give more powers to the local government units in accelerating economic development and upgrading the quality of life for the people in the community [10].”

More so, the Congress clearly and expressly granted the City Government of Davao, through the City Council, police power by virtue of Section 16(oo) of RA 4354 or the Revised Charter of the City of Davao which states that:

To enact all ordinances, it may deem necessary and proper for the sanitation and safety, the furtherance of the prosperity, and the promotion of the morality, peace, good order, comfort, convenience, and general welfare of the city and its inhabitants, and such others as may be necessary to carry into the effect and discharge the powers and duties conferred by this Charter; and to fix penalties for the violation of ordinances, which shall not exceed a two hundred-peso fine or six months imprisonment, or both such fine and imprisonment for a single offense, in the discretion of the court.

Thus, the Local Government of Davao is vested with authority to exercise police power. However, is the proposed amendment a valid exercise of the police power?

In Social Justice Society vs. Atienza [11],the High Court ruled that “local governments may be considered as having properly exercised their police power only if the following requisites are met: (1) the interests of the public generally, as distinguished from those of a particular class, require its exercise and (2) the means employed are reasonably necessary for the accomplishment of the purpose and not unduly oppressive upon individuals. In short, there must be a concurrence of a lawful subject and a lawful method”

The Zoning Ordinance, particularly the classification of the portions of the Shrine Hills as a UEESZ, was enacted for the purpose of promoting sound urban planning, ensuring health, public safety and general welfare of the Dabawenyos. The SangguniangPanlungsod is pressed to make measures to protect the Dabawenyos from catastrophic devastation in case of manmade or natural disasters that would put the lives of Dabawenyos in peril. “Wide discretion is vested on the legislative authority to determine not only what the interests of the public require but also what measures are necessary for the protection of such interests.Clearly, the Sanggunian was in the best position to determine the needs of its constituents. [12]”

In the same case, the Court upheld that the Zoning Ordinance is a valid exercise of Police Power. It ruled that;

“The means adopted by the Sanggunian was the enactment of a zoning ordinance which reclassified the area where the depot is situated from industrial to commercial. A zoning ordinance is defined as a local city or municipal legislation which logically arranges, prescribes, defines and apportions a given political subdivision into specific land uses as present and future projection of needs. As a result of the zoning, the continued operation of the businesses of the oil companies in their present location will no longer be permitted. The power to establish zones for industrial, commercial and residential uses is derived from the police power itself and is exercised for the protection and benefit of the residents of a locality. [13]” (emphasis and underscoring supplied)

Property rights are not superior to the general welfare that is meant to be protected by the Local Government Unit.

The vintage case of People vs. Julio Pomar [14], still finds application in the case at hand with regard to the exercise of police power. The Court, in this case, held that:

“It is a well settled principle, growing out of the nature of well-ordered and civilized society, that every holder of property, however absolute and unqualified may be his title, holds it under the implied liability that his use of it shall not be injurious to the equal enjoyment of others having an equal right to the enjoyment of their property, nor injurious to the rights of the community. All property in the state is held subject to its general regulations, which are necessary to the common good and general welfare.Rights of property, like all other social and conventional rights, are subject to such reasonable limitations in their enjoyment as shall prevent them from being injurious, and to such reasonable restraints and regulations, established by law, as the legislature, under the governing and controlling power vested in them by the constitution, may think necessary and expedient. The state, under the police power is possessed with plenary power to deal with all matters relating to the general health, morals, and safety of the people, so long as it does not contravene any positive inhibition of the organic law and providing that such power is not exercised in such a manner as to justify the interference of the courts to prevent positive wrong and oppression.” (emphasis and underscoring supplied)

The Zoning Ordinance and the proposed amendment, therefore, is a valid exercise of police power as laid down by the Supreme Court in both cases. Thus, just compensation is not necessary.

Again, as clearly ruled by the Court in the case of Social Justice Society vs. Atienza [15], “Compensation is necessary only when the State’s power of eminent domain is exercised. In eminent domain, property is appropriated and applied to some public purpose. Property condemned under the exercise of police power, on the other hand, is noxious or intended for a noxious or forbidden purpose and, consequently, is not compensable. The restriction imposed to protect lives, public health and safety from danger is not a taking. It is merely the prohibition or abatement of a noxious use which interferes with paramount rights of the public” (emphasis supplied)

ON THE SECOND ISSUE, considering the foregoing discussions, the proposed amendment did not violate the due process of law. In fact, it complied with the requisites of due process, that are, (1) There is a reasonable relation between the purposes thereof and the means employed for its accomplishment (Lawful Subject); and (2) The means employed must be reasonably necessary for the accomplishment of the purpose and not unduly oppressive upon the persons concerned (Lawful Means).

The proposed amendment complied with the requirements: Lawful Subject – the proposed amendment seek to protect the welfare of the Dabawenyos residing within the UEESZ and below the UEESZ for possible danger of erosion as manifested in the recent incident. Lawful Means – as discussed in the case of Social Justice Society vs. Atienza, the zoning ordinance is a valid means to promote the lawful subject and that is the means adopted by the Sanggunian.

Hence, due process was not violated.

Further, the proposed amendment did not violate the equal protection of the law. Basically, DMC UPDI raised that it is only Shrine Hills that was declared UEESZ and no other areas within Davao City was declared as UEESZ.

The Shrine Hills was declared UEESZ through a terrain analysis conducted by the Mines and Geosciences Bureau. It was found out that most of the areas found in Shrine Hills are highly susceptible to landslide. Hence, the declaration as UEESZ. If in the future, there will be areas found to be highly susceptible to environmental danger through a terrain analysis, the same will be declared as UEESZ and will be subjected to THE SAME RESTRICTIONS and THE SAME PENALTIES.

Just because there is only one UEESZ declared under the Zoning Ordinance means it was passed with partiality on the part of the City of Davao against DMC UPDI or other developers within that area.

Thus, equal protection of the law was not violated.

[1] https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/16694/cherry-hills-main-case-still-in-court

[2] https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/43720-ghost-of-cherry-hills

[3] DMCI UPDI Position Paper dated June 19, 2018

[4] G.R. No. 166923, November 26, 2014

[5] Section 458(a), Republic Act No. 7160 otherwise known as “The Local Government Code of 1991”

[6] Social Justice Society vs. Jose L. Atienza, G.R. No. 187836, November 25, 2014

[7]BienvenidoSalandanan, et al. vs. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 127783, June 5, 1998

[8] Section 1, Article VI, 1987 Philippine Constitution

[9] G.R. No. 156052, February 13, 2008

[10] Section 5(c), Republic Act No. 7160 otherwise known as “The Local Government Code of 1991”

[11] G. R. No. 187836, November 25, 2014

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid

[14] G.R. No. L-22008, November 3, 1924

[15] G.R. No. 156052, February 13, 2008

Download the position paper here.